CiRA Reporter

CiRA Reporter

Feature

November 6, 2024

Creating an Artwork That Brings Science Closer to Home: The Story of Its Creation and the Thoughts Behind the Artwork (Part 1)

In the first part, we asked her about the impetus for planning this artwork and the difficulties she encountered during the production process.

Kinuko Kasama

How did you come up with the idea of planning this work?

The project started in April 2023 with support from the SECOM Science and Technology Promotion Foundation. Dr. Minari wanted to create an artwork that could encourage the general public to think about our relationship with science and cells, so he proposed this project.

As to why he asked me to be involved, he said, "Kasama, you're neither a scientist nor a researcher, and your strength is that you understand the general public's point of view." I understood his intention was that I might be able to communicate in a different way than before to the public by adding my nonscientist point of view because experts often use inaccessible jargon and assume a scientific viewpoint unconsciously. I have a master's degree in international relations from Japan and a master's degree in political philosophy from the UK, so I can read papers in English. We wanted to take advantage of my experience, so I was assigned the mission of researching foreign artworks about science and society, and to find and coordinate with artists.

What did you think when Dr. Minari proposed this project?

I thought it sounded interesting, so I wanted to do it. However, after thinking about it for a while, I wondered whether I could do it. I also felt uneasy about it. The concept was simple, but I realized it would be very challenging to incorporate it into a work of art.

First, to engage people to think about science, we must include scientific elements in the design. However, what we wanted to avoid was for the work to be expressed only in scientific perspectives so that the viewer would feel that they don't understand it, or that it's irrelevant to them. We also needed to ensure that the content didn't lead the viewer in a particular direction by expressing "this is the message of this work" or make them feel negative or uncomfortable.

Everyone should feel free to look at it any way they like, but there are subtle hints and tricks scattered throughout that should make you think about science in various ways. I wanted to keep this kind of balance in mind.

What made this project even more difficult was that the artists had to understand the concept behind the creation of the work and then come up with their own ideas of what they really wanted to convey and express to create an attractive piece. My most critical mission was to find and coordinate artists who would agree with our project and make it happen. I soon realized what a difficult task I had undertaken, but it was already too late (laughs).

Why did you choose art as a tool to get the public thinking about science?

I'm a layperson when it comes to science. Scientific discoveries seem like something you see in the news one day, and before you know it, they become technology that we take for granted in everyday life. But in some cases, they can change my or someone else's values and life, so there are many topics worth reflecting on, whether or not we're experts.

Nevertheless, it's a challenge to communicate science well to the general public. Most people will break out in a cold sweat when confronted by books and papers on science. Even if you learned biology or chemistry at school, and although you might understand things like the structure of a cell, it's hard to find a personal connection or to think deeply about questions like, "What's science to me?" Because of that, we decided to create this work: to build a bridge to get the general public to think about science.

With art, there's no jargon, so it's accessible to both children and adults. It can also transmit ideas and concepts across time and without language. It's also a great way to express our relationship with science, which has no correct answer. A design that attracts people makes them want to see it time after time. If people could see it regularly, they'd have a much better chance to think about it.

You asked the creative unit tupera tupera, comprising Tatsuya Kameyama and Atsuko Nakagawa, to create the artwork. What made you ask them to do this?

My child is a big fan of tupera tupera's picture book Obake Da Jyo, which has many circles on the endpaper. While I heard the pattern was inspired by frog eggs, I couldn't help but think of them as cells—simple but very powerful and attractive cells.

In the past, tupera tupera also created science-themed works and, for example, was involved in exhibits at Miraikan. In an interview, they said, "It's interesting because you learn a lot when you dive into new things." They aren't picture book writers per se, but as a creative unit, are involved in various activities, ranging from designing stages for theater to designing characters for TV programs to conducting workshops.

I was sure tupera tupera would understand the concept of this project and say it was interesting. Moreover, when I realized that tupera tupera lives in Kyoto, I knew there would be no other choice.

(From left) Kinuko Kasama; Tatsuya Kameyama and

Atsuko Nakagawa from tupera tupera; and Jusaku Minari

What was tupera tupera's reaction when you commissioned the work?

Actually, we were almost rejected several times (laughs). What we asked for was a work about cells, not an explanation of cells like a picture in an encyclopedia, but rather an expression of "the concept cells represent," a work with no specific message, but not entirely without one, that would stimulate the viewer to think in different directions about the relationship between science, society, and themselves. These ambiguous requests made tupera tupera very worried.

It was a challenging time for tupera tupera and us. We repeatedly told them what we wanted to do through our work and explained the characteristics of cells described in any materials or papers we could find that might help them imagine. We also gathered an image collection of cells, etc. We shared everything we could think of. When I asked them about it later, they said "We were scared because Kinuko sent them materials endlessly" (laughs). So, I think I was quite desperate at the time.

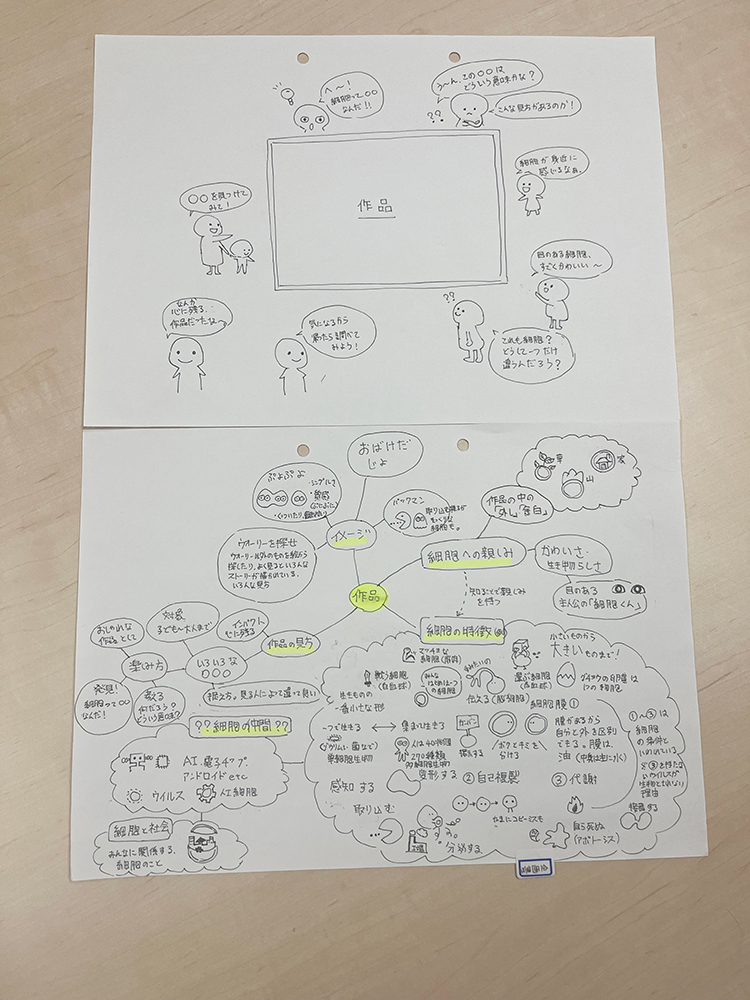

An example of the project proposal created by Kasama

It’s amazing how detailed and illustrated all the proposals are.

Thank you very much. These proposals are love letters with our thoughts in them. We made these proposals hoping something in them might inspire tupera tupera, or they could find something they wanted to express. They are very busy people, and I thought I had to send them something organized, so I also made a concept list. I wrote down what I wanted to convey, how I wanted the general public to see it, how I wanted people to feel when they saw it, and anything else that came to mind. I thought it might be rude, but I also thought it would be helpful, so I made lots of proposals.

Why do you think tupera tupera ultimately accepted the project?

I think it was because we agreed on the importance of everyone thinking about “what cells and science and technology that deal with them mean to me” and because they found it interesting to create a new artwork to stimulate thinking, but didn't seem to have an answer. They have always challenged themselves in various ways.

After many meetings, I was happy when tupera tupera said, "We'll think about the work." The key points for the work were that "it should make people feel familiar with cells and think about them as a personal matter." They came up with three rough drafts that met these points, tupera tupera said. "We didn't know how to incorporate the fact that it seems like there's a message, but there also isn't, and that was the most difficult part." Then Dr. Minari and I chose one that suited the concept best.

-

Interviewed and written by Yoko Miyake

Science Communicator, CiRA International Public Communications Office

(Translation: Kelvin Hui Ph.D., CiRA Research Promoting Office)